|

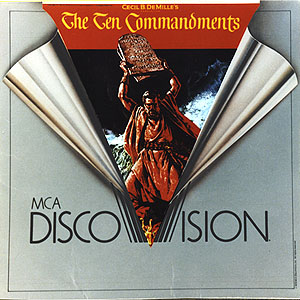

With the current hypesters declaring the laserdisc to be the video format of the 1990s, a consumer

is apt to think that this high-tech medium begins and ends with Pioneer Electronics. But the faithful know that - in the

beginning - there was DiscoVision!

Although demonstrated to the press on December 12, 1972 at Universal City, California, the first

production machines and discs didn't go on sale to the public until December 15, 1978 at Rich's Department Store in Atlanta,

Georgia. A second debut followed on May 20, 1979 in Seattle, Washington, at the Bon Marché department store. Soon

after, test cites across the country were established. With 90 more lines of resolution than video tape, the option of

stereo sound on some discs, and laserdisc movies available at a fraction of the cost of pre-recorded video tapes,

DiscoVision seemed to be what Chicago Today called "the movie buff's salvation."

Although demonstrated to the press on December 12, 1972 at Universal City, California, the first

production machines and discs didn't go on sale to the public until December 15, 1978 at Rich's Department Store in Atlanta,

Georgia. A second debut followed on May 20, 1979 in Seattle, Washington, at the Bon Marché department store. Soon

after, test cites across the country were established. With 90 more lines of resolution than video tape, the option of

stereo sound on some discs, and laserdisc movies available at a fraction of the cost of pre-recorded video tapes,

DiscoVision seemed to be what Chicago Today called "the movie buff's salvation."

The Philips/Magnavision disc playing machines were beautiful to look at, and there

was something magical about having your favorite movies contained on a silver disc riddled with little microscopic

pits. Problems with the system immediately clouded the highly successful launchings by MCA and Philips. The smooth

playing of a videodisc must be a happy marriage between disc and machine. MCA was refining disc mastering and

production at the plant in Carson, California, while Philips was going through he same process on machines, half

way around the world at its plant in Eindhoven, Netherlands - thus hindering communication and cooperation between the

two elements.

Laser Lock - the most common problem with DiscoVision - occurs when the machine locks on a

single frame and repeats it over and over, like a broken record. This phenomenon usually occurs when variations of

pit size and alignment on a disc fall outside the beam's ability to focus on it. Today's players allow for a much wider

tolerance in disc mastering, while the early Philips machines had a beam so tight that even minor deviations would

result in a disc that locked. Improper tracking was only part of the problem, however.

Some machines were overheating to the point of cooking discs, while others wouldn't play at all.

MCA, on the other hand, had its own set of nightmares in California at the disc=pressing plant

in Carson.

Disc mastering and replication is a very involved and difficult process. When explained in a

logical manner, it all seems very simple and straight forward. However, even with a more tolerant machine, strict

specifications must be followed, or degradation of the disc master, stamper or physical pressing can occur at any

number of points. What actually constituted a "clean" room for production of discs was highly debatable in the

beginning. The fact is that dust and even tiny insects were infiltrating the process at the Carson plant, making

quality control a near impossibility for DiscoVision. Defect rates could run as high as 70 to 90 percent, with a

total pressing of 2000 sides yielding only 200 passable units. [Our failure rate on purchased discs was one in three.]

In addition, some sides seemed to refuse all attempts at mastering. Plant workers trying to

assemble 100 sets of Jaws might find themselves with more than enough copies of Sides One, Three and Five, but

unable to find enough Twos and Fours to complete the order. The large, impressive 1978 DiscoVision catalogue gave the

impression that a treasure trove of software was now available and that hundreds of new titles would be available

shortly. However, with all the complications occurring with production, the torrent of new titles turned to a mere

trickle. Disc player owners returned time and time again to outlets to find the same tired selection.

Laser rot, a condition still prevalent today, is usually a result of oxidization on the

reflective coating of the disc. The process can begin as early as a week from pressing, or not show up until

years later. The videophile, rushing home to still-step through the shower sequence in Psycho, might find

himself with several sides that left the Carson plant in excellent shape, but were now covered with video and audio snow.

MCA was well aware that its expertise lay with the production of entertainment, not in

manufacturing. On September 29, 1979, MCA and IBM formed DiscoVision Associates, a 50/50 joint venture, with IBM

taking over much of the responsibility for manufacturing, as well as further research and development of the infant

medium. Also in the wings was the Universal Pioneer Corporation, formed in October 1977, as a joint venture between

MCA and Pioneer Electronics for the research and development of laser players for industrial applications. Supplied

with all the knowledge that MCA and Philips had gained through early development, the Japanese firm was quick to

pinpoint what went wrong in the beginning. With major funding from MCA, Pioneer was soon producing superior machines,

and in October 1980, opened a disc-pressing plant in Kofu, Japan, with a truly clean room resulting in disc runs with

only a fraction of the defects found at the Carson plant.

By the early 1980s, it was clear that America's choice for home video was the VCR, not the

optical disc player. With the medium still far from perfect, and with IBM wanting out of the disc manufacturing

business, MCA felt it best to divest DiscoVision Associates from the plant in Carson, and turn the entire matter of

disc production over to Pioneer. In March 1982, DiscoVision Associates ceased manufacturing activities of

laser-optical discs. Pioneer took over Universal Pioneer Corporation, which then became Pioneer Video Corporation and

the MCA DiscoVision disc was - for all intents and purposes - a dead issue.

Almost.

By the mid-1980s, opinion began to shift in favor of the videodisc. RCA, in a monumental

advertising blitz, released its highly touted CED disc player. But despite all the PR, chatter in the consumer

market was that if you wanted to go videodisc - go laser. In 1984, Pioneer dropped the price of their LD-660 to

just below $300, a move that caused many - including myself - a jump into the medium for the first time. I had no

idea what the difference was between extended play (CLV) and standard play (CAV), but tattered DiscoVision pressings

of Slap Shot and Saturday Night Fever changed my life forever.

I sculpt famous people for a living. I tried using the freeze frame on my VHS player as

research; but the image was fuzzy and the tape heads would eventually damage my very expensive prerecorded tapes.

With the discovery of the Still function on a CAV disc, I found I could hold an image for as long as I needed,

without any damage or wear to the disc. Better still, the image on my screen was as good as, if not better than, some

of the 8x10s I once worked from.

I wanted more of these standard play discs, but where was I supposed to find them? Remember

this was 1984, and we were still years away from the Criterion Collection; the only CAV feature film in the Pioneer

catalogue was the Special Edition of Raiders of the Lost Ark. The end of DiscoVision had also brought about

the temporary end of movies in the standard-play mode. Pioneer figured, rightly, that the average consumer just

wanted to watch a movie, not dissect it to death on an interactive disc. The market was still too small to cater to

the film enthusiasts who did.

And so, The DiscoVision Collector was born.

And so, The DiscoVision Collector was born.

My first stop on the DiscoVision trail was MCA. Marty Henry, an MCA employee who had been

around for much of the DiscoVision era, informed me that any and all remaining DiscoVision pressings would be in

the hands of Pioneer at the Carson plant.

Barbara Zeitiger, a DiscoVision employee who stayed on after Pioneer took over, told me

that all the remaining stock of DiscoVision had turned into a liability for Pioneer. Aware that most would be

returned as defective, Pioneer felt it was better to save paperwork and shipping expenses by simply destroying the

pesky software. A wise move for Pioneer; a sad state of affairs for the collector.

Calls to North American Philips (Magnavox) in Knoxville, Tennessee, yielded only CLV

DiscoVision pressings still in stock, and a search of all video outlets in surrounding areas of California only nabbed

me CAV copies of Smokey and the Bandit II and The Jerk. Not much of a find for someone looking for

CAV pressings of To Kill a Mockingbird and The Bride of Frankenstein.

Then I got in touch with Court Addinger, the original DiscoVision buyer for the Bon

Marché stores in Seattle, and now the owner of his own store, The Videophile. It seemed I wasn't the

only person in pursuit of CAV DiscoVision. Addinger had stopped selling DiscoVision altogether because the

prices people were willing to pay for it were climbing daily. He had no idea what the value might be and

wanted to wait until the market had leveled off. I was told a good copy of Abbott and Costello Meet

Frankenstein (a title I wanted badly) might go for as high as $1000, while a perfect copy of The Bride of

Frankenstein might fetch $500. A copy of Thoroughly Modern Millie had just been sold in New York City

for $1500.

A little rich for my blood.

Eventually I was steered over to Charles Shishkevish, who now owns and runs Ceba Video in

Fort Washington, Maryland. An avid DiscoVision collector and trader, Charles not only had the titles I longed for at

a fair price, but he was wiling to guarantee them as first quality, or my money back! The core of my collection came

from Shishkevish, and in the light of what I was about to learn from collecting on my own, it was money well spent.

If you want something on DiscoVision, and want to save yourself a great deal of agony, talk to Shishkevish. [ed: I

should point out here that Charles was the source of my first DiscoVision titles in the mid 80s - titles that I still

own to this day.]

As time went on, I became relentless in my quest for DiscoVision. My work takes me to

various parts of the United States, and in every new town I always make a point to contact Magnavox dealers and

video stores. I found a great deal of DiscoVision, usually in batches of five to ten titles, usually from people

who had traded-up with local dealers. There was also a Magnavox dealer here and there who had a box of it gathering

dust in his back room. The sad part was that the vast majority was just as defective as I thought it would be.

The distressing thing about collecting laserdiscs is that, unlike other collectibles, there

is little on the surface of an out-of-print disc to distinguish it from trash or treasure. A totally defective copy

of Earthquake I recently purchased looks like the clean pressing given to me by a Magnavox dealer in Texas.

Unless the disc is cracked, or has some obvious surface flaw, you won't know what you're getting until you play it.

Another diversion for the DiscoVision collector are the titles that may have been mastered, but

never made it to actual production runs. On today's laserdiscs, if you have a movie pressed onto three sides, the

software pressed onto the fourth, Dead Side, is just a polite message telling you to flip the disc over to finish your

movie.

In the days of DiscoVision, sides left over from production runs, test pressings, or other

material, were sprayed with a clear plastic in order to prevent playback and pressed onto the Dead Side. Terry and

Tony Cook, two of the earliest DiscoVision devotees, learned quickly that a little rubbing alcohol and a soft cloth

would remove the coating and allow the sides to be played. Good sides from other movies, General Motor's promotional

material, sales lectures, government training films, and even sides of movies never thought to have been mastered

were discovered. Titles that have been found include, if only in part, The Monkey's Uncle, The Prince and

the Pauper, Sugarland Express, Anne of a Thousand Days, and a CLV Side One of Bullitt.

Single-sided test pressings of Sweet Charity and The Andromeda Strain are also known to exist.

Discovery of these titles has led many to speculate that perhaps everything in the initial

DiscoVision catalogue may have been mastered, but not pressed for the sale of discs and machines in 1978. For

years, rumors have persisted among collectors that titles may have been pressed, but not shipped out because of

production errors or else recalled immediately after shipment. Others tell tales of preproduction promotional

pressings sent out to dealers.

Dana Brown, a technician working in the DiscoVision mastering department, confirms that

some titles may have been mastered, in part, for test purposes, while Ron Hensley, a production manager at the

plant said, "If a title was committed to the mastering process, it would have been mastered in total, not in part."

We do know that certain titles had problems with various sides and perhaps some of these might never have made it

into full production. This would explain the odd side, here and there, of unreleased titles find on Dead Sides.

As for recalls, both workers at DiscoVision and dealers in the consumer market deny that there was ever any

formal recall of a title. Some titles had more problems than others, but disc buyers were so anxious for new

titles that most sets sold out as quickly as they arrived. Ron Hensley went on to state: "If there had been some

defect in the mastering major enough to justify a recall, we would have caught it long before an actual production

run."

As for the question of limited pressings for dealer circulation, Court Addinger says that

"If there had been any advance dealer copies of a title, I would certainly have received one as the buyer for the

Bon Marché stores. Such a thing never existed. MCA Universal was very concerned about possible copyright

infringement with home video. Nobody was really sure how it would work in practice. They even wanted us to sign

a document saying that we wouldn't allow anyone to play a disc in the store for any longer than 30 seconds, so as

not to constitute a public showing. If they were that concerned about copyrights, they certainly would never have

allowed advance pressings. If they did exist, I never saw one, nor did any other dealer I was in contact with."

Ken Crane Jr., of the Ken Crane Home Entertainment chain in Southern California confirms

this, as do the many other dealers I have spoken with over the years.

Another problem concerning the announced VS pressed controversy is the fact that - to this

day - the laserdisc division of MCA Home Video continues to retain the original DiscoVision catalog numbers issued

to titles still in print (Frankenstein, Thoroughly Modern Millie, American Graffiti), even

with titles that were originally announced on DiscoVision but never saw the light of day, such as Double Indemnity,

and the remake of Dracula. [ed: MCA/Universal stopped using DiscoVision numbers in 1992.] Ed Rubio, an

early staff member at DiscoVision, told me that the first title they tried to master, but just couldn't get to

work, was the W.C. Fields / May West farce My Little Chickadee. Although it appeared along with a number

of other mock=up disc boxes for the 1974 press showing, it was not included in the original 1978 Silver Catalogue,

nor was it mentioned in any subsequent DiscoVision listings. I found this story hard to believe, but when MCA

recently announced it as an Encore Edition, there was a DiscoVision number attached to it. Go figure.

Another problem concerning the announced VS pressed controversy is the fact that - to this

day - the laserdisc division of MCA Home Video continues to retain the original DiscoVision catalog numbers issued

to titles still in print (Frankenstein, Thoroughly Modern Millie, American Graffiti), even

with titles that were originally announced on DiscoVision but never saw the light of day, such as Double Indemnity,

and the remake of Dracula. [ed: MCA/Universal stopped using DiscoVision numbers in 1992.] Ed Rubio, an

early staff member at DiscoVision, told me that the first title they tried to master, but just couldn't get to

work, was the W.C. Fields / May West farce My Little Chickadee. Although it appeared along with a number

of other mock=up disc boxes for the 1974 press showing, it was not included in the original 1978 Silver Catalogue,

nor was it mentioned in any subsequent DiscoVision listings. I found this story hard to believe, but when MCA

recently announced it as an Encore Edition, there was a DiscoVision number attached to it. Go figure.

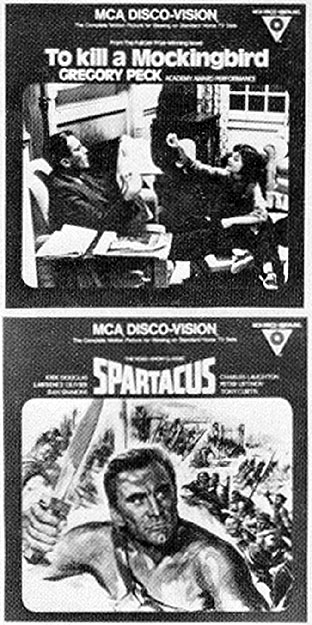

One collector claims to have held an entire eight-sided, CAV DiscoVision edition of

The Godfather; another, a ten-sided, CAV DiscoVision copy of The Ten Commandments. We know that

boxes and labels were prepared for the entire initial catalogue, and that many of these boxes turned up at trade

shows and conventions; but without physical evidence of actual sides, it's hard to prove or disprove anything.

Until such proof does arrive, these lone DiscoVision sightings can only serve as come-ons for the rabid collector

who longs for the only complete DiscoVision collection in the world.

Paperwork that would confirm a number of archival questions (number of units of a title

that left the factory, actual release dates, mastering information) is still, I believe, on file with MCA. I have

talked with a number of people there, but have been unable to gain access to it. I believed for a long time that

the information didn't exist, that it had gone the way of Charles Foster Kane's beloved Rosebud. It is my hope

that someday somebody will be granted permission to print it so that many of the DiscoVision myths could be laid

to rest forever.

I hope what I have written so far will discourage you from ever wanting to start a

DiscoVision collection. If it has, on the other hand, piqued your curiosity, here are a number of hints when

looking for DiscoVision.

1) Get yourself an older "hot tube" laser player. The Pioneer LD=660, certainly the most

forgiving on older DiscoVision sets, can be picked up used for as little as $75. The new solid-state players pick

up a great deal more, and what looks good on a hot tube player might not look so good, ore even play, on a new model.

On the other hand, I'm told the LD-S2 handles many of the early pressings quite well. If you don't have the $3500

for the LD-S2, however, you might want to go with the LD-660.

2) Don't expect Criterion Collection quality from these early pressings. These are antiques,

not video standards. I still prefer my DiscoVision Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein to the Encore Edition

re-release. I think the transfer was much better on the original. But it does contain light speckling here and there

that would now send a disc buyer screaming back to the video store. I do have sides on sets that are as clean and

clear as anything produced now, but finding a copy of a five-sided movie on DiscoVision with all sides that clear

just isn't realistic.

3) There are still a number of titles that were originally pressed on DiscoVision that

are not likely to be re-pressed in the near future. If you desire only one or two titles and are not out to start

a collection, call or write Charles Shishkevish at Ceba Video and get a price quote. It is the quickest, and in

the long run the most painless, way to acquire the titles [ed; While Charles still has a large collection of discs,

has stopped selling DiscoVision.]

4) If you buy from an ad in a video publication, don't be surprised if that "perfect copy

of Rollercoaster on DiscoVision" isn't. The truth is that there are a few dealers who will try to get

away with murder. "It must be your machine," or "It played fine on my disc player" are all phrases you are likely

to hear. They may be telling the truth, but if you're in California and they're in New York, there is little you

can do except pass the deception along to another collector. (Of course, your entire laserdisc collection will

develop laser rot and you will burn in video hell forever if you do it.)

5) If you buy from someone who has no idea of what he is selling (i.e, swap meet, thrift

store, garage sale) try not to spend more than $5 to $15 per set. Finding all good sides on any DiscoVision pressing

is unlikely, and you will probably have to double sets up in order to get an acceptable title. My perfect copies

of Jaws and The Hindenburg are both made up of five discs - one good side per disc. To get three

good sides on a five-sided CAV pressing is about average. There are certain sides, however, that turn up bad no

matter how many copies you run across (The Greek Tycoon Side Two, The Sting Side One, Rollercoaster

Sides Two and Five), so even if a title is rare, be careful what you pay.

6) If you buy from a local store that deals with used discs, they will likely know two

things about DiscoVision: A) It's very collectible; B) Most of what's around is defective. If they're going to

charge you what they think it's worth ($10 to $50 per side), scan it in the store first, or make

sure you can return it if it shows up as defective on your machine. If it's being sold "as is, chances are good

it will have some problems (speckles, audio distortion, laser rot, or laser lock). Even rare titles drop

drastically in value if they have known bad sides, so be careful. It's a gamble and the odds aren't in your

favor.

7) If they can be obtained at a fair price, don't let sets with known bad sides scare

you entirely away. You can always trade the good sides with other collectors for good sides or even titles

you may be looking for. A good Side Five of The Hindenburg (often defective) could be traded for an

entire movie of lesser value (Smokey and the Bandit or Jaws). Many times collectors will only

trade, so start building up a disc pool to draw from.

8) Don't forget those Dead Sides! I have completed several defective sets by

using discoveries made on Dead Sides. Some collectors have even put together entire movies by combining them.

Of course, as the laserdisc market grew, the demand for more programs in CAV increased.

Starting with their ground-breaking CAV editions of King Kong and Citizen Kane, the Voyager Company

demonstrated what the techs at MCA DiscoVision knew from the beginning - the laserdisc was capable of a great deal

more than simple playback of movies. With various studios now releasing Criterion-like editions of classic films,

the Standard Play CAV disc is no longer a rarity, but a solid member of the laserdisc family.

So why, with so many new CAV editions coming out - why - with the advent of freeze frame

capability for CLV discs - why would I want to keep on collecting sets of DiscoVision? Well, for one, I've been

doing it so long, it's a habit.

Two, I suffer from collector's mentality: An insane desire to acquire something that is

rare, unavailable to the general public, or impossible to find. DiscoVision is all these things. Don't get me

wrong; I'm a film buff first, and a DiscoVision collector second. A complete, defect free, set of the entire

DiscoVision library is not my goal. My heart does not yearn for a flawless copy of VD: The

Hidden Epidemic. However, a defect-free CAV DiscoVision pressing of either Psycho or The Lost

Weekend might make my heart skip a beat.

Three, DiscoVision is history. It represents the first, hesitant steps into something

that had never been done before. Almost everyone I interviewed connected with the project ended up saying the

same thing in one form or another: "It was one of the most exciting experiences in my professional career; it

was the most challenging project I had ever been connected with." It's a shame the beginning of the laserdisc

was so bumpy. The press release for MCA's 75th anniversary begins its entry into the home video market with the

release of 25 pre-recorded tapes in 1981 - not with DiscoVision in 1978. Getting anybody at Pioneer to talk

about it is almost impossible, it's the bastard child nobody wants to own the village idiot everyone wishes would

go away.

There are just over 80 full-length movies released in CAV by DiscoVision. I have managed

to put together about 55 clean, playable titles. It's more than I ever thought I would locate, and I'm glad to have

the old boys around, as forerunners to a medium I dearly love. What the long-playing record is to the CD disc,

DiscoVision is to the laserdisc industry. George Jones, former executive vice-president of DiscoVision, recently

told me, "Everyone forgets that there was no information on how to make a laserdisc. We had to invent everything.

Nobody knew if it would really work, or how it would work." Taking that into consideration, it's pretty amazing it

went as well as it did."

|

Although demonstrated to the press on December 12, 1972 at Universal City, California, the first

production machines and discs didn't go on sale to the public until December 15, 1978 at Rich's Department Store in Atlanta,

Georgia. A second debut followed on May 20, 1979 in Seattle, Washington, at the Bon Marché department store. Soon

after, test cites across the country were established. With 90 more lines of resolution than video tape, the option of

stereo sound on some discs, and laserdisc movies available at a fraction of the cost of pre-recorded video tapes,

DiscoVision seemed to be what Chicago Today called "the movie buff's salvation."

Although demonstrated to the press on December 12, 1972 at Universal City, California, the first

production machines and discs didn't go on sale to the public until December 15, 1978 at Rich's Department Store in Atlanta,

Georgia. A second debut followed on May 20, 1979 in Seattle, Washington, at the Bon Marché department store. Soon

after, test cites across the country were established. With 90 more lines of resolution than video tape, the option of

stereo sound on some discs, and laserdisc movies available at a fraction of the cost of pre-recorded video tapes,

DiscoVision seemed to be what Chicago Today called "the movie buff's salvation." And so, The DiscoVision Collector was born.

And so, The DiscoVision Collector was born. Another problem concerning the announced VS pressed controversy is the fact that - to this

day - the laserdisc division of MCA Home Video continues to retain the original DiscoVision catalog numbers issued

to titles still in print (Frankenstein, Thoroughly Modern Millie, American Graffiti), even

with titles that were originally announced on DiscoVision but never saw the light of day, such as Double Indemnity,

and the remake of Dracula. [ed: MCA/Universal stopped using DiscoVision numbers in 1992.] Ed Rubio, an

early staff member at DiscoVision, told me that the first title they tried to master, but just couldn't get to

work, was the W.C. Fields / May West farce My Little Chickadee. Although it appeared along with a number

of other mock=up disc boxes for the 1974 press showing, it was not included in the original 1978 Silver Catalogue,

nor was it mentioned in any subsequent DiscoVision listings. I found this story hard to believe, but when MCA

recently announced it as an Encore Edition, there was a DiscoVision number attached to it. Go figure.

Another problem concerning the announced VS pressed controversy is the fact that - to this

day - the laserdisc division of MCA Home Video continues to retain the original DiscoVision catalog numbers issued

to titles still in print (Frankenstein, Thoroughly Modern Millie, American Graffiti), even

with titles that were originally announced on DiscoVision but never saw the light of day, such as Double Indemnity,

and the remake of Dracula. [ed: MCA/Universal stopped using DiscoVision numbers in 1992.] Ed Rubio, an

early staff member at DiscoVision, told me that the first title they tried to master, but just couldn't get to

work, was the W.C. Fields / May West farce My Little Chickadee. Although it appeared along with a number

of other mock=up disc boxes for the 1974 press showing, it was not included in the original 1978 Silver Catalogue,

nor was it mentioned in any subsequent DiscoVision listings. I found this story hard to believe, but when MCA

recently announced it as an Encore Edition, there was a DiscoVision number attached to it. Go figure.